How to Tell If Wood Furniture Is Worth Refinishing

Is that flea market find worth your time and effort? Learn how to tell if you have a diamond-in-the-rough or fodder for the trash pile.

When you find a piece of wood furniture that needs a little love, it's really tempting to just fork over the cash and take it home as your next pet project. But wait, says woodworking expert Teri Masaschi, author of Foolproof Wood Finishing. There are some things you need to consider first before you decide to refinish.

Julia Robbs

Is the Piece Painted?

"Beware of things that are painted," Masaschi says. "There's usually a reason for that." Paint can hide a multitude of sins, including burns, missing veneer and water stains.

"You're far better off buying something that has old dirty varnish on it that just needs to be stripped," she says. "It's clear, you can see through it to whatever's underneath, and stripping old finish is really easy — it typically comes right off with products you can buy at the hardware store."

Is the Construction High-Quality?

Look for signs that the piece was made before 1950, maybe even 1960. "That’s when particleboard and laminate surfaces and cutting corners came along," Masaschi says. Generally, even mass-produced furniture from before 1960 is sturdier and better made than today's cheap furniture — your find doesn't have to have antique value to be a great vintage piece that will give you years of service.

Still, you should be careful with really old pieces, mostly those made before 1850, because refinishing them yourself can hurt their value. If you have any questions at all about the value of your piece, consult an expert before you get started. “The basic rule of thumb is, if the piece was made before 1850, you want to do some homework on whether it should be conserved rather than restored — meaning to preserve and stabilize the piece as it is now,” she says. “If it’s been in the family a while, it’s worth finding out before you do some damage.”

To muddy the waters a bit, there are some more recent pieces by prominent makers — for example, from the Art Deco, midcentury modern, and Arts and Crafts periods — that command high prices and shouldn’t be touched. If you suspect there’s something unusual or distinctively well-made about your piece, go with your gut and ask someone who knows.

What to Look For

Dovetail joints. This construction detail is your first key to the piece’s age and quality of craftsmanship. Dovetail joints are strong and require skill to produce, so they’re generally a sign of a well-made piece. Hand-cut dovetails can date an older American piece to before 1890, although hobbyists and specialty makers still use them. “There’s no hard and fast rule, but hand dovetailing was really no longer done in factories after that date,” Masaschi says. Hand dovetails are slightly irregular and the pins are thin and tapered. Wider, uniform machine-cut dovetails were common in factory-made pieces from 1890 until the modern era.

If a piece has no dovetails, it can still be a candidate for refinishing if it’s sturdy and well-designed, but it’s not likely to be an old piece with antique value.

Scott E. Kriner, Fox Chapel Publishing

Hand dovetails (top piece) are slightly irregular and the pins are thin and tapered. Wider, uniform machine-cut dovetails (bottom piece) were common in factory-made pieces from 1890 until the modern era.

Solid wood or plywood backing. Look at the backside of your piece, including the insides and backs of drawers if applicable. Solid wood backing indicates a piece is likely pre-1880s; plywood came into vogue around the turn of the 20th century. Particleboard means you probably have something made in the 1960s or later — the era of “cutting corners,” as Masaschi says.

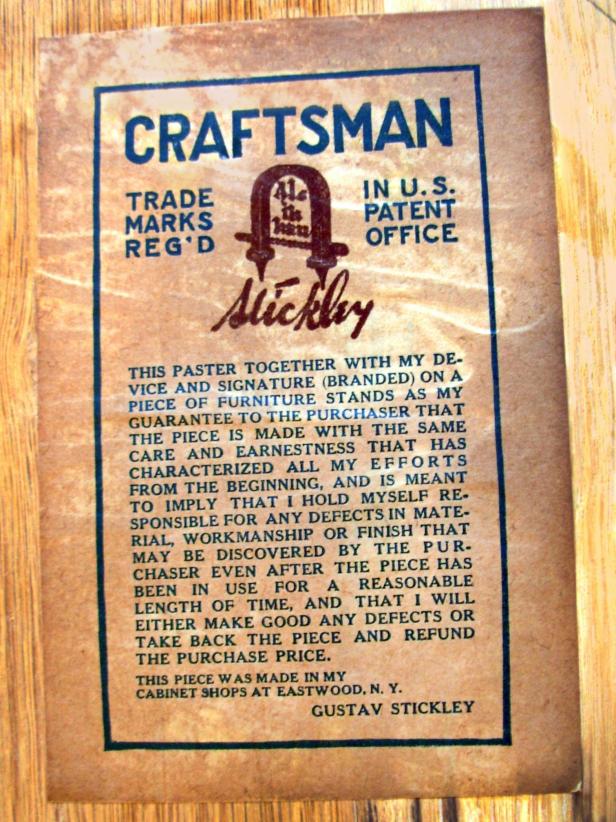

Inscriptions or manufacturer’s stamps. If you’re lucky, a piece will have a marking on it indicating its origin. Early pieces that were handcrafted will sometimes bear an inscription from an individual furniture maker, a clue to its value that should be examined by a professional appraiser. “If they’re really old, it could be just a pencil signature on the inside of a drawer,” Masaschi says. “But by the time you hit the turn of the 20th century, makers were using paper labels, which then progressed into brass plaques tacked onto the insides of drawers or on the back of a piece. Then in the 1950s and 1960s, they were using spray-on stencils.” Keep in mind that sometimes suites of furniture had only one piece marked, so if your piece got separated from its mates, you may have nothing to go by.

Mass-produced pieces from the turn of the 20th century onward will often bear a label from the manufacturer, such as “Larkin Soap Co.” or “Cadillac Cabinet Company.” This is a nice little piece of history — but also tells you how common the piece is, which can help you determine whether you should refinish it yourself. Generally, mass-produced pieces up until the 1950s and 1960s (when particleboard and cheaper, flimsier construction techniques became popular) are great candidates for refinishing.

Look for original hardware and other details. Does the piece have its original hardware? What style is it? Solid cast-brass or wooden pulls mean the piece is likely old; using a collectibles reference guide, you can identify their style and hence their age range. Common style examples are Chippendale, Hepplewhite, Sheraton, Federal, Depression-era, Victorian and Queen Anne.

Emily Followill Jenkins

A few other details can help you date a piece:

- Marble-top dressers and what Masaschi calls “battleship” beds with giant headboards and footrests are almost exclusively from the Victorian era (late 1800s). If you feel comfortable with handling any ornate detailing on these pieces, they’re usually fine to refinish yourself.

- Any piece on casters (wheels) is typically pre-1930s.

- If you have a dresser with a mirror attached on a harp, your piece was made around the turn of the 20th century. If you have a set with a separate mirror that hangs on the wall above the dresser, you can date that to the 1940s or later.

Is It in Good Condition?

When deciding if your furniture piece is worth refinishing do what Masaschi calls "the rickety test." Put your hands on it, rock it back and forth, and test the drawers, if there are any, to see how much swaying is going on. If the piece isn't sturdy, you'll probably have to take it apart and re-glue it using clamps, and not everyone has the skill for that — or the workspace, for that matter.

If you need an expert to re-glue your piece for you, expect to pay based on how complicated the piece is. "It takes time to knock the piece apart and completely remove the old glue and start over," Masaschi says. "Re-gluing a chest of three drawers could easily cost $400 to $500."

What Will It Look Like When You’re Done?

When a piece has been neglected for decades, it’s tough to tell what it will look like once it’s refinished. To get an idea of what your piece will look like refinished, find a protected spot where the original wood is visible, such as the back of a solid-wood drawer front, underneath the top surface of a chest of drawers or the backside of a leaf in a drop-leaf table. Make sure that you like the look of the grain and that you understand what color you’ll come out with in the end — old wood often finishes much darker than newly milled wood.

Here are the characteristics of several common types of wood on older furniture pieces:

Fox Chapel Publishing

Cherry

Fox Chapel Publishing

Walnut

Fox Chapel Publishing

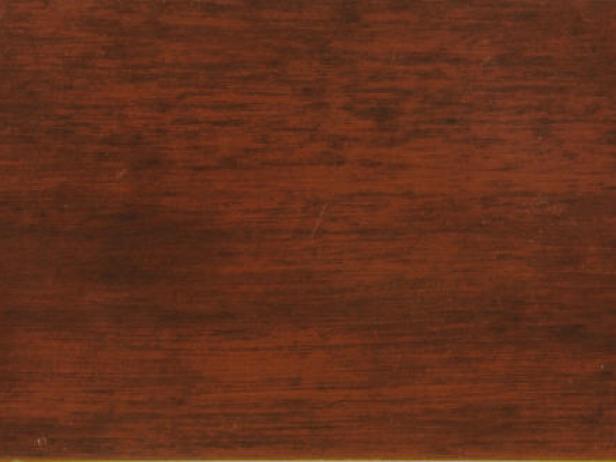

Mahogany

Cherry (Image 1) is a very smooth wood with a mild grain that can be stained in a variety of colors. “But if it’s 100 years old and you’ve stripped it, it’s going to be very dark,” Masaschi says.

“Walnut (Image 2) has a more lively grain than cherry or maple,” Masaschi says, “but it’s one of the few wood types that actually gets lighter over the years.” The natural rich brown color limits the range of tones you can achieve with stain.

“With old mahogany (Image 3), there’s no way around it — it’s going to be very reddish,” Masaschi says. “You can go reddish red or brownish red, but you’ll never get anything else out of it.”

Fox Chapel Publishing

Pine

Fox Chapel Publishing

Maple

Oak

Most old pine (Image 1) pieces were painted right away, so it’s rare that you’ll come across one you’ll want to strip and refinish. But if you do, expect a honey brown color that’s darker than new pine.

Maple (Image 2) pieces made from the 1890s through the 1920s are often a beautiful figured bird’s eye or tiger maple and will have a strong yellow tone if you refinish. Plain maple from the 1960s, which was often stained an orangey color, can be stripped and made more modern with a light brown stain.

Oak (Image 3) is the staple wood of Victorian furniture. “Old furniture is often made of quarter-sawn oak with bold flecking in it,” Masaschi says. “If you refinish it, you’ll get that really beautiful old tiger oak grain that’s golden in color.”

How Complicated Is the Refinishing Going to Be?

Make sure you're prepared for the level of involvement it will entail restoring the piece to its former glory. Here are some signs that your project may require extra steps or advanced techniques:

- It features deeply carved or applied filigree. It's usually very time-consuming to strip out the old finish from all the nooks and crannies, and refinishing it will also be very tricky.

- Different parts of the piece need different applications. For example, a chair with ornate sides or slats may need a delicate touch on the ornamental parts, but multiple coats of polyurethane on the arms so they'll be durable.

- It has slats or spindles set close together. To strip that off and refinish it, you almost have to use a spray gun.

- It's made from random boards not all from the same tree. That's one of the ugly surprises you sometimes get after stripping. You'll either have to like it the way it is or spend a lot of time trying to stain it to make it look more uniform. That's a pretty complicated finishing process.

Bottom line: If you aren't sure what you have, consult a competent professional for advice. And just because a piece has potential, don't feel obligated to bite off more than you can chew. "I always tell my students, be prepared to walk away," Masaschi says. "Buy the piece for what it is rather than what you think you can make it — you can get lost in the fantasy about what it used to be."