A Vegetarian Can Be a Good Host. Really.

It can seem hard to host a plant-based meal. It isn't.

When I was 13, I stopped eating meat for ethical reasons. That led to a few intense conversations with my mother (who worried about my health) and friends (who assumed I was going to lecture them about their choices), but it didn’t change much for anyone else. I started taking a daily multivitamin, grew accustomed to eating salads and side orders of fries at restaurants and got into the habit of having just-in-case snacks before weddings and formal dinners so that my hosts wouldn’t have to go out of their way for me. Pretty easy.

Dating and eventually marrying my husband, Joe, was pretty easy, too. He was not vegetarian — he comes from a meat-loving Italian foodie family — but courtship doesn’t exactly require Lady-and-the-Tramp-style dinners from the same plate. In fact, his fondness for preparing and serving complicated meals was one of the reasons I fell for him: For one of our first dates, he shopped his way through our suburban English town and spent all afternoon simmering a glorious, veggie-friendly soup. When he made sauces for other meals, he’d set aside and re-season meatless portions just for me. At that point I had spent a decade urging people not to think about what I needed, and that attention was unexpected and wonderful.

Joe’s kitchen skills were our holiday gatherings’ not-so-secret weapon for a very long time. The division of labor when we were having guests over for a big meal — at which we assumed some sort of meat was expected — was straightforward: I would run the errands and prep our apartment, and he would take care of our omnivorous friends and family. He’d tell me what to pick up from our local butcher, and while I loathed that job, I told myself I was being a good partner and conscientious host in carrying it out.

As the years went by, Joe quietly and gradually became uncomfortable with eating meat, too. The sausages and cold cuts he’d stashed in a corner of the refrigerator disappeared, and his orders at restaurants started sounding more like mine. He is not quite vegetarian now — if pressed, he’ll explain that he is still OK with consuming some shellfish.

Eddy Chen

That sounds straightforward — but is occasionally deeply awkward in practice. Why on earth would people who feel that it’s wrong to eat animals serve them to their guests? Well, as anyone who’s swept politics under a holiday table can tell you, large gatherings have a lot of moving parts. When Christmas dinner is already a precarious balance of remarriages, former estrangements and delicate new friendships, it can be hard to say, “Hey, so the Polish kielbasa you’ve loved and praised for years that made you feel seen and forged a much-needed bond between your family and mine won’t be here tonight or ever again." (For example.)

Because vegetarianism is comparatively rare in Western cultures and we Americans are rather fixated on festive meats, it can also seem hard to host a plant-based meal without inviting an agonizing group dissection of one’s personal beliefs or suggesting that one doesn’t give a damn if one’s guests are unsatisfied.

The predictable (and only) solution is to cook your a-- off — or as Joe would say, "Just make tasty stuff and hold the meat. Simple."

As college-age Joe intuited, making me feel welcome and valued was as easy as finding out how he could make me happy and demonstrating that he would take the time to do it. I filled the kielbasa-shaped hole in my stepmother’s heart by learning more about her holiday favorites and cramming my house with meatless dishes she loves. I finally acknowledged that though I’d spent decades trying to be a frictionless vegetarian guest, thoughtful hosts had been accommodating me all along — and I could accommodate them, with cookoff-conquering chili (for my sisters and my stepbrother’s girlfriend) and mushroom stroganoff (for my mom and stepfather) and homemade blood orange sorbet (for my dad). Asking someone for pointers on how to make them a fabulous meal isn’t an imposition: It’s an act of love.

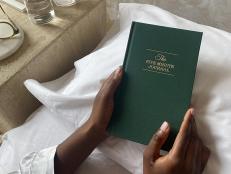

Adam Rose

I am neither Dutch nor Catholic, but a Dutch Catholic priest named Henri Nouwen defined generosity in a way that resonates strongly with me. “Hospitality,” he wrote, “means primarily the creation of free space where the stranger can enter and become a friend instead of an enemy. Hospitality is not to change people, but to offer them space where change can take place. It is not to bring men and women over to our side, but to offer freedom not disturbed by dividing lines.”

I can set the table for that.